Can't Disrupt This

Disrupting the huge profits of academic publishers requires new ‘basement market’ strategies

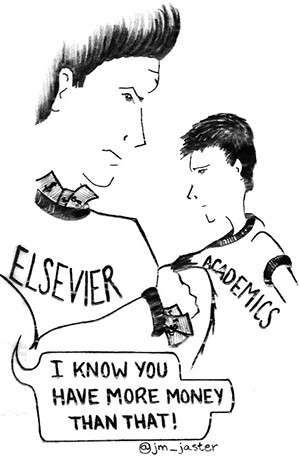

# Elsevier and the 25.2 Billion Dollar A Year Academic Publishing Business

Twenty years ago (December 18, 1995), Forbes predicted academic publisher Elsevier’s relevancy and life in the digital age to be short lived. In an article entitled “The internet’s first victim,” journalist John Hayes highlights the technological imperative coming toward the academic publisher’s profit margin with the growing internet culture and said, “Cost-cutting librarians and computer-literate professors are bypassing academic journals — bad news for Elsevier.” After publication of the article, investors seemed to heed Hayes’s rationale for Elsevier’s impeding demise. Elsevier stock fell 7% in two days to $26 a share.

As the smoke settles twenty years later, one of the clear winners on this longitudinal timeline of innovation is the very firm that investors, journalists, and forecasters wrote off early as a casualty to digital evolution: Elsevier. Perhaps to the chagrin of many academics, the publisher has actually not been bruised nor battered. In fact, the publisher’s health is stronger than ever. As of 2015, the academic publishing market that Elsevier leads has an annual revenue of $25.2 billion. According to its 2013 financials Elsevier had a higher percentage of profit than Apple, Inc.

Brian Nosek, a professor at the University of Virginia and director of the Center for Open Science, says, “Academic publishing is the perfect business model to make a lot of money. You have the producer and consumer as the same person: the researcher. And the researcher has no idea how much anything costs.” Nosek finds this whole system is designed to maximize the amount of profit:

I, as the researcher, produce the scholarship and I want it to have the biggest impact possible and so what I care about is the prestige of the journal and how many people read it. Once it is finally accepted, since it is so hard to get acceptances, I am so delighted that I will sign anything — send me a form and I will sign it. I have no idea I have signed over my copyright or what implications that has — nor do I care, because it has no impact on me. The reward is the publication.

Nosek further explains why researchers are ever supportive by explaining the dedicated loyal customer base mantra, “What do you mean libraries are canceling subscriptions to this? I need this. Are you trying to undermine my research?”

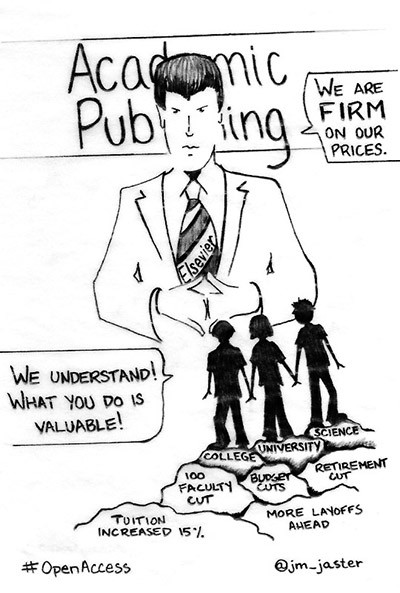

In addition to a steadfast dedication by researchers, the academic publishing market, in its own right, is streamlined, aggressive, and significantly capitalistic. The publishing market is also more diverse than just the face of Elsevier. Johan Rooryck, a professor at Universiteit Leiden, says, “Although Elsevier is the publisher that everybody likes to hate, if you look at Taylor & Francis, Wiley, or Springer they all have the same kind of practices.”

Heather Morrison, a professor in the School of Information Studies at the University of Ottawa, unpacks the business model behind academic publisher Springer and says:

If you look at who owns Springer, these are private equity firms, and they have changed owners about five times in the last decade. Springer was owned by the investment group Candover and Cinven who describe themselves as ‘Europe’s largest buy-out firm.’ These are companies who buy companies to decrease the cost and increase the profits and sell them again in two years. This is to whom we scholars are voluntarily handing our work. Are you going to trust them? This is not the public library of science. This is not your average author voluntarily contributing to the commons. These are people who are in business to make the most profit.

Should a consumer heed Morrison’s rationale and want to look deeper into academic publishers cost structure for themselves one is met with a unique situation: the pricing lists for journals do not exist. “It’s because they negotiate individually with each institution and they often have non-disclosure agreements with those institutions so they can’t bargain with knowing what others paid,” says Martin Eve, founder of the Open Library of the Humanities.

In addition to a general lack of pricing indexes, the conversation around the value of a publication is further complicated by long-term career worth. David Sundahl, a senior research fellow at the Clayton Christensen Institute for Disruptive Innovation, says:

We actually understand how money passed through to artists who wrote music and authors who wrote books — but it is not clear how the value of a publication in a top tier journal will impact someone’s career. Unlike songs or books where the royalty structure is defined, writing a journal article is not clear and is dependent not on the people who consume the information but rather deans and tenure committees.

Disruption Doable?

It is precisely the prior lack of a pricing and value barometer that leads to the complexities associated with disrupting the main players in academic publishing. “Adam Smith’s invisible hand works to lower prices and increase productivity but it can only do so when valuation or pricing is known and the same thing is true for disruption. If you don’t know how to value something, you actually don’t have tiers of a market,” says Sundahl.

If a disruptive force was to significantly change academic publishing it needs to happen in a market that is currently underserved or undesirable by the large-scale publisher. “Disruptive innovation is usually driven by a group who can’t afford to build something that is as big, fancy and sophisticated as the existing solution — they then have to find a market where either people don’t have anything available to them or they are satisfied with something less than perfect,” says Sundahl.

Should academic scholarship keep existing in a similar trajectory as in the past decades Sundahl finds incumbents (existing big publishers) almost always win when competition takes place along those sustaining strategy lines. “To revolutionize academic publication, a new system would need to be developed in a basement market which would eventually enable people to gain enough credibility doing this new solution. People would then begin to value this lower end, well done research, and that is when the world starts to change,” says Sundahl.

The prior is exactly what large entities like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation or perhaps even top tier research one (R1) universities can’t do. “They have to play the game the way the winners are already playing it. Incumbents almost always win under those conditions,” says Sundahl. And to further complicate matters, junior colleges and community colleges, which perhaps would represent fertile grounds to be served by a newer, “basement market” entrant, may be less likely to spearhead this new outlet themselves due increasing government constraints focused nearly exclusively on job placement and starting salaries in lieu of a research-based, theoretical curriculum.

Open Access Packs a Punch

Driven by the lopsided power structure the move toward open access and the unrestricted access to academic information has been exponentially growing. Perhaps it is, itself, a “basement market” for leveling the academic publication environment and creating a market where respect and credibility can be fostered, grown and transitioned into the existing academic prestige, merit, and tenure conversations.

“The open access environment is one of the more fertile environments for people to be thinking: if we don’t like the old way, what should the new way look like,” says Heather Joseph, executive director at the Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition (SPARC). Joseph finds that the quantifiable numbers of open access journals speak for themselves and says, “You can look at the number of strictly open access journals if you look at the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ). When it started tracking open access journals there were a few dozen and now they list over 10,000 open access journals.”

The push toward open access is not only growing in sheer numbers of journals but also in an increasingly confrontational strategy that academics leverage against large publishers. “At the moment, the Netherlands, the whole country, has said to Elsevier that we want all of our researchers to be able to publish open access in your journals at the same rates we would pay for a subscription last year and if you can’t do that we’re going to cancel every one of your journals, for all of our universities nationwide,” says Eve. “They have a few days left to resolve this, and it looks like they are going to cancel all the Elsevier journals.”

Rooryck found his recent very public decision to step down and move his Elsevier journal Linga to open access met with complete support from the other six editors and 31 editorial board members. “The process went very easily. We were all aware of the pricing and Elsevier’s practices and within a week everyone agreed to resign,” says Rooryck. Eve’s platform, the Open Library of Humanities, will now house the new open access iteration of Lingua, which will be called Glossa. Eve says, “Right away it is 50% cheaper to run it through us then when it was with Elsevier. So anybody subscribing to it already sees 50% more revenue.”

Rooryck finds the move toward broad open access a natural progression and says:

The knowledge we produce as academics and scientists should be publicly available in the same way we have a company that delivers water to our faucets and electricity to our home. These are things we have a right to. Public knowledge and education is a human right and it should not come with a profit tag of 35%.

Although it appears open access has the ability to simultaneously diffuse academic knowledge to a larger body of readers and cut costs significantly, many feel that the for profit academic publishers are still situated to continue into the near future. Joseph says:

I think the play for most smart commercial publishers is to try to preserve the current environment for as long as they can: delay the policy changes, delay the culture changes and to be working on things like tools and services applying to aggregation of data, where they are then embedding themselves more deeply in the workflow of researchers and becoming essential to researchers in a different way.

If you are no longer essential to researchers in the, ‘you have to publish in my journal in order to get tenure and promotion’ what do they replace that with? I think the smart publishing companies like Elsevier, like Springer, who are very smart in that regard, have been thinking about where they can go to be playing a role of continuing to be seen as essential by the research community once they are no longer playing the role of providing assessment.

Onward and Upward

“In the US Congress we have been finally making progress with the Fair Access to Science and Technology Research (FASTR) bill. It moved through the committee it was referred to in the Senate and is poised to move out of the Senate and potentially be considered by the House and hopefully pass. Ten years ago, I would have said we didn’t have a chance to do a stand-alone bill,” says Joseph.

Perhaps the recent congressional support Joseph refers to is one more verifying measure that the majority of articles will be moving toward an open and accessible framework. Many in the academic community hope that this government support signals the reprioritization of a research framework and the switching of the guard. And while the prior is extremely important, others in the academic community are hoping to grow “basement markets” from the ground up.

The Center for Open Science, which provides seed funds to startups in the academic scientific research space, is led by Nosek and focuses on aligning scientific values to scientific practices. “The open science framework is just a means at connecting all the research services that researchers use across the entire research life cycle,” says Nosek.

Nosek is optimistic about the evolution of technology in open science and says, “There are a lot of startups going at different parts of the research life cycle. Whether it is publication and what a publication means, or looking at full articles and whether you can make articles convey information in smaller bite size pieces.” Nosek tells me that there are so many solutions happening in research right now and mentions it is hard to judge what the true solutions will look like:

I sometimes think some of the ideas haven’t a chance, but what do I know? I could be completely wrong about it. And that is the whole point — do some experimentation and try out ideas. And the fact is there are a lot of people who see what the problems are and have a unique sense of a potential solution — it is a very lively time to try out different answers.

Time will tell if open access will be the needed disruption to allow the academic environment to right itself or if a new market emerges from startup incubators like the Center for Open Science. Regardless of how the future vision is realized, most in the academic community hope that the new iteration of scholarly articles and publishing will do more good toward humankind than that of a hefty profit margin.

Image header credit: Alan Levine; creative commons license.