The Command Line

How to make friends with a computer

Drew Holgate, co-founder of Rounded Globe, begins a series of occasional posts highlighting the significance of Linux, the free software movement, and other techy issues that the educated public should be aware of, but aren’t.

“Don’t you have to use the command line?” or “Isn’t Linux a command line?” are concerns people often raise when thinking about switching to Linux.

And they tend to be mollified with something like “No, you never need to touch the command line. You can do everything you’d do on any other computer without ever seeing the command line”. Which is perfectly true. But we see the unspoken question in their eyes; “If you don’t have to use it, then why on earth do you?”.

They don’t actually ask it because they’re afraid we’ll talk more about Linux.

And it’s understandable, to their eyes the command line looks archaic — it’s what people used in the 70s and we’ve got graphics now — why would you use something so crude?

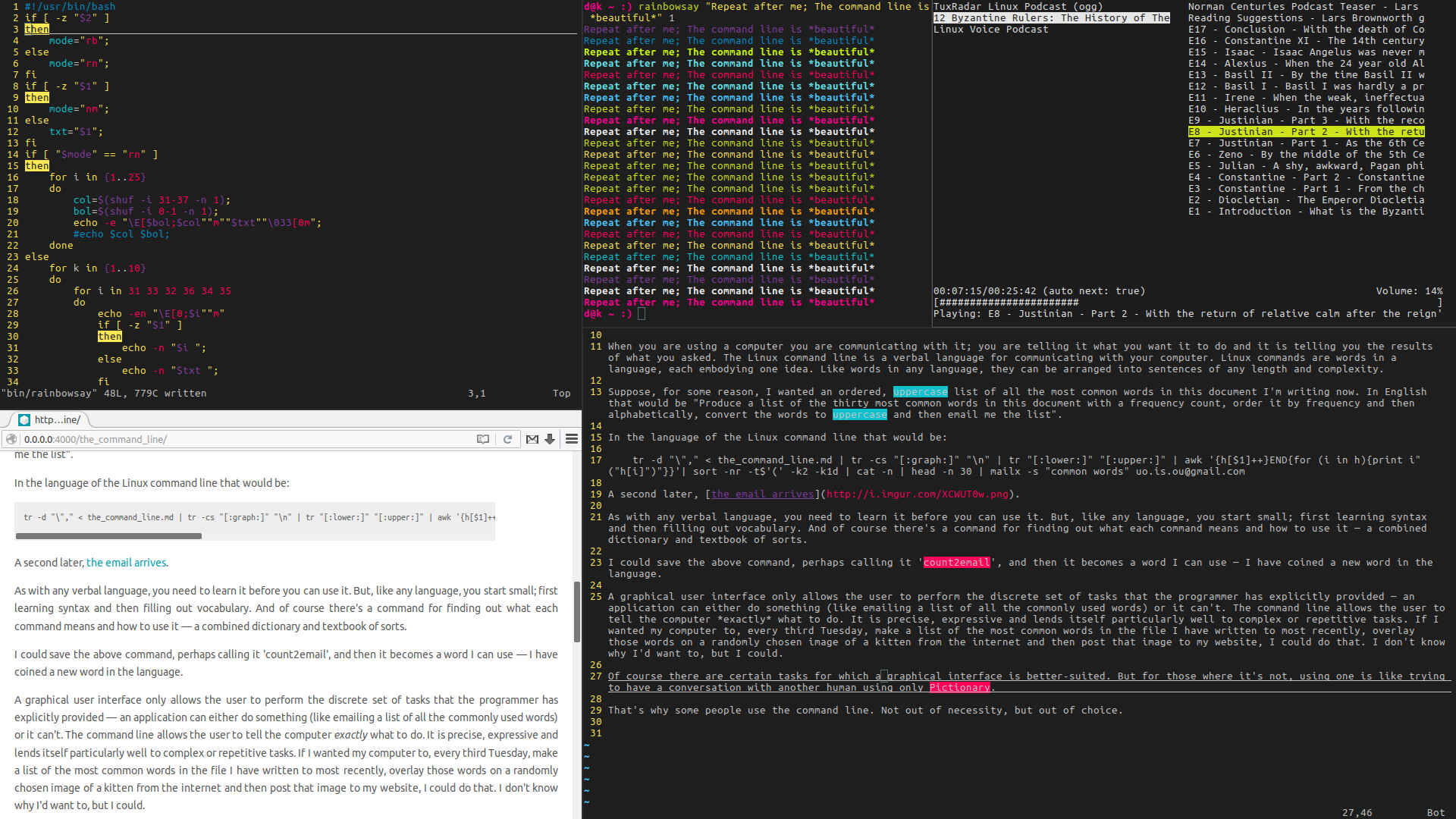

When you are using a computer you are communicating with it; you are telling it what you want it to do and it is telling you the results of what you asked. The Linux command line is a verbal language for communicating with your computer. Linux commands are words in a language, each embodying one idea. Like words in any language, they can be arranged into sentences of any length and complexity.

Suppose, for some reason, I wanted an ordered, uppercase list of all the most common words in this document I’m writing now. In English that would be “Produce a list of the thirty most common words in this document with a frequency count, order it by frequency and then alphabetically, convert the words to uppercase and then email me the list”.

In the language of the Linux command line that would be:

tr -d "\"," < the_command_line.md | tr -cs "[:graph:]" "\n" | tr "[:lower:]" "[:upper:]" | awk '{h[$1]++}END{for (i in h){print i" ("h[i]")"}}'| sort -nr -t$'(' -k2 -k1d | cat -n | head -n 30 | mailx -s "common words" uo.is.ou@gmail.com

A second later, the email arrives.

As with any verbal language, you need to learn it before you can use it. But, like any language, you start small; first learning syntax and then filling out vocabulary. And of course there’s a command for finding out what each command means and how to use it — a combined dictionary and textbook of sorts.

I could save the above command, perhaps calling it ‘count2email’, and then it becomes a word I can use — I have coined a new word in the language.

A graphical user interface only allows the user to perform the discrete set of tasks that the programmer has explicitly provided — an application can either do something (like emailing a list of all the commonly used words) or it can’t. The command line allows the user to tell the computer exactly what to do. It is precise, expressive and lends itself particularly well to complex or repetitive tasks. If I wanted my computer to, every third Tuesday, make a list of the most common words in the file I have written to most recently, overlay those words on a randomly chosen image of a kitten from the internet and then post that image to my website, I could do that. I don’t know why I’d want to, but I could.

Of course there are certain tasks for which a graphical interface is better-suited. But for those where it’s not, using one is like trying to have a conversation with another human using only Pictionary.

That’s why some people use the command line. Not out of necessity, but out of choice.

Header image: Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie, the inventors of Unix. CC BY-SA license.