Changing Faces of Britain's Natives

Gollum and Bilbo Baggins emerge out of Edwardian preshistoric scholarship

Simon J. Cook, Rounded Globe author, shares some of his research into the history of British conceptions of prehistory and the genesis of Tolkien’s hobbits.

Late-Victorian histories of the English began in the woods of Schleswig, before the migration to the British Isles. But around 1900 historians decided that English history proper should begin with the foundation of the modern state in the fourteenth century. What came before was deemed not only barbarous but insufficiently documented. The story of ancient Britain, and of the peoples who settled it, was left to a motley crew of archaeologists, folklorists, philologists and, increasingly, writers of fiction.

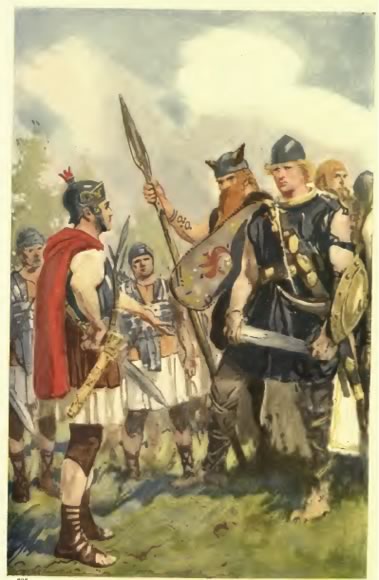

Picture from: Our Island Story. A History of England for Boys and Girls, by H.E. Marshall, illustration by A.S. Forrester (London, 1905).

In the first section of my Rounded Globe essay on J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lost English Mythology I’ve discussed some facets of the early twentieth-century search for the ancient English; in this post I track the changing face of Britain’s natives. The picture above depicts a sort of ancient ‘close encounters’ moment: native Britons watch the arrival of the Roman fleet of Julius Caesar. This captures the conventional Victorian image of the Romans bringing civilization to a savage island.

Compare the primitive Britons above, barefoot and attired in rude animal skins, with the blond giants below. Although this second picture was published earlier, it embodies a newer kind of historical thinking. These iron-age warriors are still Britons, but they are no longer natives.

Picture from: Beric the Briton. A Story of the Roman Invasion, by G.A. Henty, illustrator unknown (London, 1893).

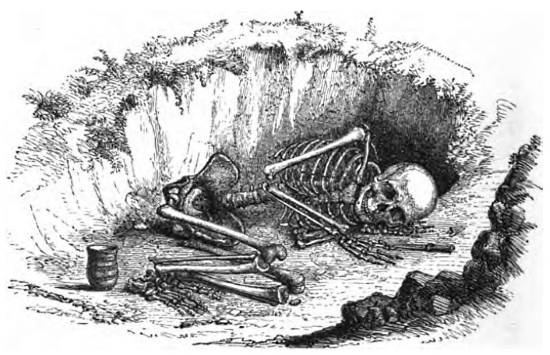

For much of the nineteenth century it was assumed that Britain had been settled for only a few generations before the coming of the Romans. But this view became untenable after 1877 and the publication of Canon William Greenwell’s British Barrows. From his meticulous and extensive archaeological excavations, Greenwell drew the conclusion that prehistoric long barrows were not only older than round barrows, but had been built by a different people.

Image from: British Barrows. A record of the examination of the sepulchral mounds in various parts of England, by W. Greenwell (Oxford, 1877).

After Greenwell it was generally accepted that the Celtic-speaking Britons, the supposed makers of the round barrows, had intruded upon an earlier population. The result was the rehabilitation of the Britons: no longer the passive victims of history, conquered and pushed aside by more vigorous peoples, the Britons became invading immigrants in their own right – ancient barbarians, maybe, yet virtuous and worthy ancestors for the modern British. In the caption of the second picture above the leading Briton declares: ‘Tell Suetonius that we scorn his mercy and will die as we have lived, free men.’

Who, then, were the newly discovered natives? With precious little archaeological or philological evidence to work with, scholars turned to fairy tales.

In 1900 John Rhys, the first Oxford Professor of Celtic, delivered the presidential address to the Anthropology section of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. His chosen theme was the value of folk tales for the study of the ancient past, and he argued that behind the ‘rabble of divinities and demons’ who disport themselves in Celtic folklore it is possible to discern the succession of peoples who have inhabited the British Isles. Welsh fairy stories, according to Rhys, contained dim memories of the native population encountered by the first Celtic-speaking intruders. The real ‘little people’, he inferred, had been ‘a small swarthy population of mound-dwellers, of an unwarlike disposition… and living underground’.

Picture from the cover of John Buchan’s The Watcher by the Threshold (London, 1902).

Rhys’ ideas seem to have sparked the imagination of a couple of young minds. John Buchan went up to Oxford in 1895. His short story ‘No-Man’s-Land’, which appeared in print seven years later, tells the dreadful story of an Oxford scholar of Northern Antiquities (like Rhys perhaps, or one of his students), who holidays in the remote Highlands of Scotland, where he encounters – and is taken captive by – ‘the Hidden People’:

Then suddenly in the hollow trough of mist before me… there appeared a figure. It was little and squat and dark; naked, apparently, but so rough with hair that it wore the appearance of a skin-covering… in its face and eyes there seemed to lurk an elder world of mystery and barbarism, a troll-like life which was too horrible for words.

While captive in their ‘hill refuge’ the Oxford scholar hears harsh words directed at the British invader, bitter curses for the Saxon stranger; and he glimpses ‘a morbid hideous existence’ preserved for centuries by these relics of a nameless past.

Buchan’s natives are the complete antithesis of the modern British subject; a sort of primitive Hyde to the modern Dr. Jekyll. One can perhaps discern a post-WWII twist to this fable in The Inheritors, the 1955 novel by William Golding (who incidentally attended the same Oxford college as Buchan). In Golding’s story the original dwellers of the land have become Neanderthals – a separate species to modern humans. But in contrast to Buchan, Golding represents these natives as a peaceful if queer-thinking folk; it is the human intruders who are violent and frightening.

Buchan’s portrayal of Britain’s ancient folk as radically different to the modern population of the British Isles made for a good story; but it did not reflect an Edwardian scholarly consensus that all newcomers to Britain had interbred with those already settled on the land. Far from being a separate species, scholars believed that much native blood flows through the veins of the inhabitants of modern Britain (the same kind of idea is now put in terms of DNA). An Englishman, a Scotsman, or a Welshmen who meets one of the forgotten little people is quite possibly discovering but a smaller version of himself. And if such encounters have today become rather rare in the fields and hedgerows of Britain, this is a familiar enough experience to many readers of J.R.R. Tolkien’s classic children’s story of 1937, The Hobbit.

Hobbits are a homely depiction of Britain’s natives. Tolkien tells us that they are a ‘little people’, who today ‘have become rare and shy of the Big People, as they call us’. But once upon a time, ‘long ago in the quiet of the world, when there was less noise and more green’, hobbits were ‘numerous and prosperous’.

Going up to Oxford in 1911, Tolkien as an undergraduate probably attended Rhys’ lectures; later, in a short essay of 1932, we find him engaging carefully with his scholarship. And it seems that Tolkien had read the Professor of Celtic’s 1900 presidential address. At one point in this lecture Rhys discusses certain ‘underground – or partially underground – habitations’ that, he believed, had been home to Britain’s natives. These abodes, he explains:

appear from the outside like hillocks covered with grass, so as presumably not to attract attention… But one of the most remarkable things about them is the fact that the cells or apartments into which they are divided are frequently so small that their inmates must have been of very short stature.

But if Tolkien first stumbled upon a hobbit hole whilst reading Rhys’ lecture, it seems likely that his imagination drew also upon Buchan’s depiction of Britain’s natives as subhuman trolls. Certainly, John Buchan was one of Tolkien’s favourite authors. Of course, Bilbo’s hole under the hill is snug and comfortable; the encounter with a ‘hideous existence’ within a ‘hill refuge’ described by Buchan finds its counterpart, not at Bag End, but in that cave deep within the Misty Mountains into which had wormed his way, long ages ago, ‘a small slimy creature’ called Gollum.

Header image: ‘Bag End’, Christopher Wagner. Creative commons license.